Heather Robinson

- Suicide and overdose deaths are the top cause of death in the first year postpartum in some states.

- Most maternal-mortality statistics don't count these deaths, but rather medical complications.

- The US encourages postpartum checkups, but the system often fails to identify signs of depression.

- Visit Insider's homepage for more stories.

Editor's note: This article mentions suicide and suicidal ideation

Ariane Audet was folding laundry in her living room when she heard her husband and her 4-month-old laughing upstairs. Suddenly, she felt at peace.

"It came to me very loud and clear: 'You see? They're happy, and they're much happier when you're not around,'" the 35-year-old Canadian American writer and photographer who lives near Washington, DC, remembers the voice in her head saying. "It was very clear I needed to die."

That was Audet's rock bottom, but her mental health had been tumbling since her daughter's birth. When her newborn was placed on her chest, she felt empty. "I was like: 'What is this? This is an alien,'" she remembers. She told Insider she cried fake happy tears – because that's what TV tells you to do – while her daughter "literally destroyed" her nipples within 24 hours.

Before her pregnancy, she imagined writing while her baby napped, but that was a pipe dream. Resentment built, and guilt about her resentment consumed her. When, on that day in the living room, her thoughts went from "I need to die" to "How should I do it?" she saved her own life by texting her therapist and going to the emergency room.

It's well documented and widely reported that pregnant and postpartum people in the US die at abysmally high rates because of largely preventable medical complications like hemorrhages and because of deep-seated cultural issues like systemic racism.

But they're also dying by suicide - and getting lost in statistics that don't consider self-harm in counts of new mothers' deaths. Advocates and maternal-mental-health professionals say new moms are silently suffering in the first year of parenthood, with each obstetrician or pediatrician appointment a missed opportunity for them to be saved.

"Why do we wait the way we wait now, until a mom has sort of fallen off the cliff of depression and then say, 'Climb out yourself, best of luck to you?'" Adrienne Griffen, the executive director of the Maternal Mental Health Leadership Alliance, told Insider. "We ought to be surrounding moms with support."

Most maternal-mortality statistics exclude suicide and self-harm

The US has the highest maternal-mortality rate of any developed country. And that rate is climbing, with women of color severely disproportionately affected.

But those stats come out of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Vital Statistics System, which tracks only deaths within 42 days of pregnancy that are directly related to the pregnancy or care.

That means the list includes death caused by medical issues like infections, preeclampsia, hypertension, sexually transmitted diseases, and blood loss. But incidental and accidental causes, including self-harm, aren't recorded.

The CDC's Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System tracks deaths during pregnancy and up to a year postpartum, but it too omits causes like suicide and overdoses.

The best gauge we have on some new moms' desperation, Griffen says, comes from Maternal Mortality Review Committees, which exist in about half of US states and are less frequently cited than the CDC's reports. Their data comes from documents like police reports, social-services reports, and autopsies, and it tracks maternal deaths up to a year postpartum.

Their data indicates suicide and overdoses, combined, are the leading cause of death among white women in the US during the first year postpartum, according to data collected from 2008 to 2017. More-recent data from states that haven't distinguished between races, including California and Illinois, indicates such deaths are the leading cause of death among all postpartum women a year out.

Among all states and races from 2008 to 2007, suicide and overdose deaths, together, were more common than deaths from preeclampsia, a life-threatening high-blood-pressure condition brought to mainstream attention by celebrities including Beyoncé and Kim Kardashian.

Though still rare, these deaths are preventable

Dying during or after childbirth in the US, though more common than in other developed countries, is still unusual. And suicide during the perinatal period is actually rarer - in Colorado, for instance, about 26 maternal deaths a year were recorded from 2008 to 2017, about eight of which were attributed to self-harm.

It makes sense, too, that the further you get out from delivery, the more likely you are to die from causes other than pregnancy and childbirth-related complications.

But while in the general population, women attempt suicide more than men but die from it less often, that's not the case during the perinatal period, when new moms resort to the most violent methods - something Griffen views as a sign of their desperation.

Suicide is preventable, and advocates say that should especially be the case during the perinatal period, given the relative frequency of hospital visits at that time.

"These women are captive in the healthcare system," Griffen said, adding: "We should be asking them how they're doing every single time. Instead, we just ignore it, and this is result."

'The only emotion you have is pain or not feeling at all'

Dr. Katherine Wisner, a Northwestern University psychiatrist who studies perinatal mental health, recalls one patient she worked with who said each morning she'd wake up and think about whether she wanted to keep living. "It's that painful," she told Insider.

Another wrote a poem with the line: "I always fight to function, I'm fighting to survive, I'm trying desperately to remember what it's like to feel alive."

"It's really hard for people to understand when the only emotion you have is pain or not feeling at all," Wisner said.

It can be especially hard in the Black community, where stigmas around mental illness can run high and support for postpartum mental health runs low.

After Kay Matthews, a Black woman in Houston who is now 42, had a miscarriage, the retired chef struggled to shower or eat or get out of bed. As her partner tried to commiserate with her over their loss, she thought: "I don't want to talk about the baby anymore. I just want to talk about what the hell is going on with me."

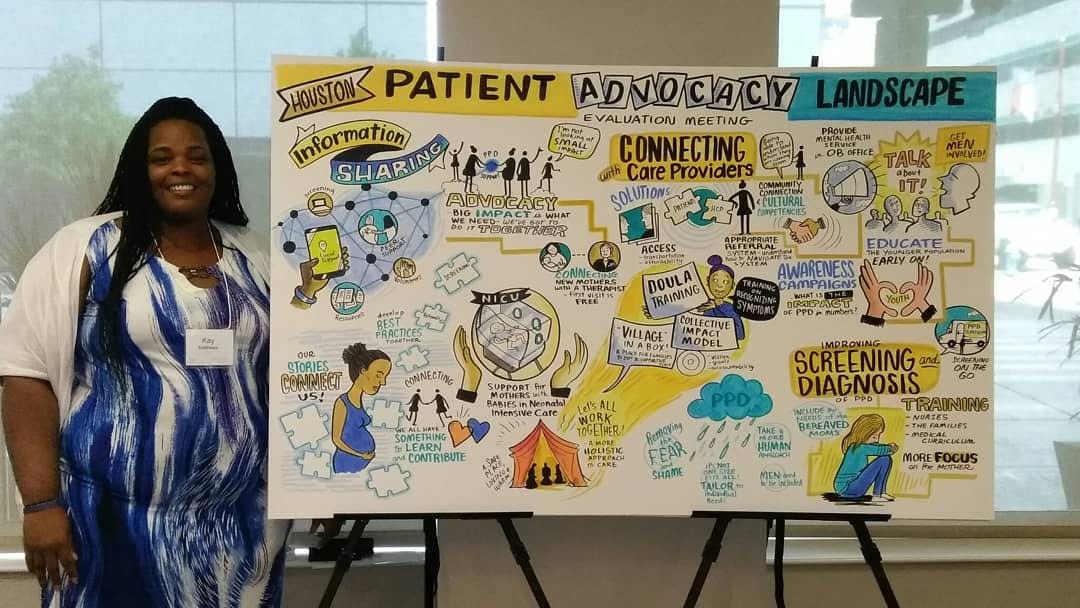

Courtesy of Kay Mathews

While she said she never experienced suicidal ideation, she's met some people who have through her Shades of Blue Project, which supports women, and particularly Black women, before, during, and after childbirth.

The population is more likely to suffer pregnancy complications and postpartum mental-health consequences - but less likely to die from self-harm. The root of that disconnect is unclear, but Griffen said it could be that they're more resilient because of the other challenges they've had to endure such as racism. Or, wrenchingly, that their higher rates of maternal death from better-documented causes like hypertension means they don't live to take their own lives.

US culture leaves moms to fend for themselves

Postpartum suicide and self-harm are related to a host of factors. People who are younger, have less social support, or have a history of abuse, poverty, or mental illness are among those at greater risk. People who've had a traumatic birth can suffer more readily too.

Some women seem to be especially sensitive to the drop in hormones after delivery. Griffen said she felt it on the operating room table after her C-section: "I was like, 'What just happened to me there?' I felt like my brain had been fried."

Courtesy of Adrienne Griffen

US culture and policies leave new moms wanting. A 2019 report found the nation was the only one of the world's 41 richest countries that had no national minimum amount of maternal leave. "Taking an hour for yourself is harder than killing yourself - that's what it came down to," Audet, the writer who lives near Washington, said.

The country's maternal-healthcare system also isn't set up with new moms at its center.

Wisner, remembers when, as a trainee, she watched a pregnant patient throw herself against a wall in a psychiatric unit. Wisner wanted to restrain or sedate the woman, but her supervisors forbade it. Straitjackets and medication, they worried, could hurt the fetus. The next day, the woman lost the pregnancy - most likely triggered by her self-harm.

"I was so angry," Wisner remembers. "I said: 'Where is the data? Where is the information that guides this decision? And doesn't a woman have a right to her own health?' After all, she's the container for the growing fetus."

While a lot has improved since then, Wisner said, new moms still report feeling abandoned after birth. Consider that, while pregnant, they have eight to 10 prenatal visits. Once they're parents, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' new recommendations encourage at least two postpartum visits.

I wasn't sad. I was pissed off, I was angry, I was overwhelmed. I was all of those other things.Adrienne Griffen, the executive director of the Maternal Mental Health Leadership Alliance

As many as 40% of all patients don't show up to one. And most of those who go on to die by suicide don't attend any.

"You have a baby, you go home, then you have to turn around a few days later and go to the pediatrician's office," Griffen said. "Moms can barely move at this point."

Slipping through the cracks, or falling through gaping holes?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that maternal-healthcare providers screen pregnant or postpartum women for depression and anxiety at least once.

When Wisner led a screening program in Pittsburgh, none of the 10,000 new moms died by suicide. All moms who screened positive for postpartum depression received home visits or phone follow-ups. But when the program closed because the grant money ran out, Wisner learned of a few deaths by self-harm. "I believe we were ending maternal suicides with extensive screening," she said.

"I think where we've failed is to really implement screenings in settings where there's an incredible disadvantage or need," she added.

Even though more than 50% of postpartum patients who die by suicide visited an emergency department within one month of their death, they weren't caught. There are no universal screening protocols, there's a shortage of mental-health providers, and maternal healthcare professionals often aren't trained in or incentivized to take the time to ask about mental health.

"Too often we put the onus on the mom to say 'I'm not doing well," Griffen said. And that's not easy.

There is still a stigma around mental illness, particularly among new parents who often feel they should be intoxicated from the smell of their newborn's soft skin and basking in the bond of breastfeeding.

Plus, you first have to recognize what you're going through. Griffen's experience didn't feel like postpartum depression. "I wasn't sad," she said. "I was pissed off, I was angry, I was overwhelmed. I was all of those other things."

Matthews couldn't even articulate what "help" would look like. "I don't even know what this is," she thought, "so how can you help me?"

Once she did get a postpartum-depression diagnosis, a whole eight months after her miscarriage, she was referred to a support group of all white women. "I couldn't relate to any of their stories," she says.

Some women, especially women of color, fear speaking up out of concern their children will be taken from them. For Michele Merritt, a professor in Arkansas, the fear was realized when Child Protective Services came knocking after she blogged about her postpartum depression.

"The fact that I almost killed myself because I was so sure I was going to fail my son was now being used against me as a potential reason to take him away from me," she wrote. After 44 harrowing days, her case was eventually dismissed.

Women who overcome the pressure to keep quiet may still not receive adequate treatment. One review of 17 studies found that, on average, only 22% of women who screened positive for depression ended up with a single mental-health visit.

There are only three inpatient perinatal psychiatric units in the US, a total of 34 beds. There are 24 outpatient units, but most states have none. "The care is out there - it's just fractured and splintered," Griffen said.

'These illnesses are temporary and treatable'

There's hope. Awareness of postpartum mood disorders is up and stigma is down. In the '80s and '90s, Wisner said, "we had to argue that there really was such a thing as depression in pregnancy and postpartum." Now the Food and Drug Administration is close to approving the first pill for postpartum depression. Online communities and resources for struggling moms abound.

Mental-health screenings during the perinatal period have increased "dramatically" across the country and are mandated in some states, Wisner said.

Griffen and others are advocating to standardize such screenings, and perinatal mental health has grown into an important subspecialty in psychiatry, Wisner said.

And, importantly, treatments - including talk therapy, telemedicine, medications, inpatient or outpatient care, and even tools like light therapy or, in the case of psychosis, electroconvulsive therapy - work.

"Most women get better. These illnesses are temporary and treatable," Griffen said. "There is no reason moms should go through this untreated." Griffen went on to have a third kid, and Audet had a second.

For Audet, relief came from inpatient care at the University of North Carolina, which, at the time, was the only such perinatal mental-health center in the US. By eight months, she felt capable of mothering, and she now runs the Faces of Postpartum photography and storytelling project to illustrate the nuances of new parenthood.

"There's a lot going on there that's not black and white," she said. "Maybe if we show these gray zones, the darkness wouldn't be so appealing."